Adalah writes about October 2000

The colonial heritage of Israel’s police

Like South Africa and the United States, Israel's police were explicitly designed to enforce racial supremacy with violence and impunity.

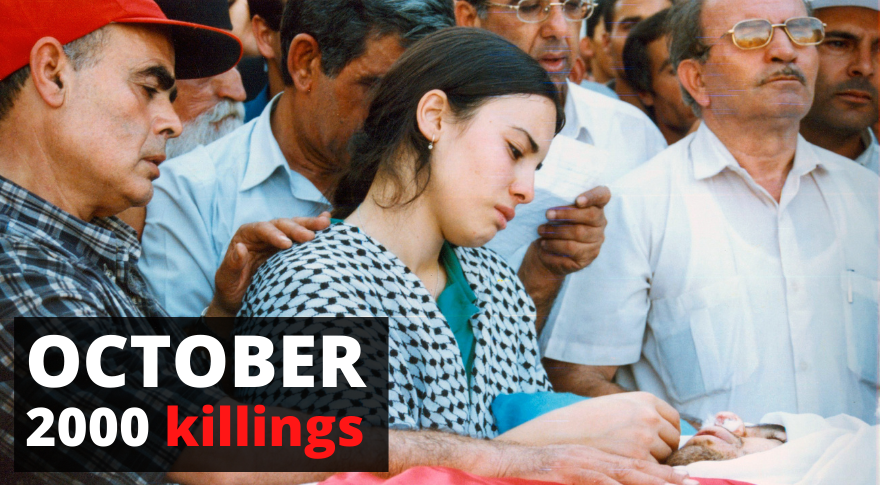

This week marks 20 years since Israeli security forces gunned down 13 Palestinian protesters, 12 of them Israeli citizens, at the start of the Second Intifada — what came to be known as the October 2000 killings. Despite massive public outcry, not a single police officer was held responsible.

Two decades on, it appears that one of the most defining moments for Palestinian citizens of Israel is still widely perceived by the Jewish public as merely an institutional failure. But to understand why Israel “failed” to put those responsible on trial, these killings — and the lack of accountability for them — must be interpreted in their full political context.

Israel’s national police force is inherently tied to the state’s legal system and to the values of the regime under which it operates — that is, the goals of ethnic supremacy for Jews and oppressive control over Palestinians.

Based on these values imprinted since its inception, the Israeli police have taken on two main roles vis-à-vis the Palestinian citizenry: suppression of any political protest against the Israeli establishment, and enforcing policies that ensure Jewish demographic, geographic, and political domination. The latter role includes, among other things, helping to carry out home demolitions and evictions of Palestinian citizens from their villages; in the Naqab/Negev, this has even led to the creation of a special police unit dedicated to demolitions and evacuations against the Palestinian Bedouin population.

Because of this dual role, violence has always been a defining feature of Israeli police behavior at demonstrations by Palestinian citizens. At the 1976 Land Day protests against the massive expropriation of land in the Galilee, the police killed six Palestinian citizens and wounded hundreds more. In October 2000, police snipers killed 13 and wounded hundreds more with live and rubber bullets. During a demolition raid on the Bedouin village of Umm al-Hiran in January 2017, where protestors were also present, police officers shot dead resident and teacher Ya’qub Abu al-Qi’an.

These violent events are not a coincidence. In fact, they accurately and deliberately reflect the role that Israel has assigned to the police since 1966, when the government ended its military rule over Palestinian communities in the state. From that moment, the police replaced the army as the major player implementing many of the state’s oppressive and geopolitical goals, which remain largely unchanged over 50 years later.

‘Guarding the land’

On Feb. 27, 1966, as Israel was preparing to wind down its military rule over Palestinian citizens, Defense Ministry officials gathered for a “top secret” meeting to discuss the role that the police would play on the day after. The protocol of the meeting is a definitive document showing that, in many respects, the government officially viewed the police force as the successor to military rule. Moreover, the document makes it clear that the main purpose of Israel’s police is not to protect the citizens they interact with, but to serve the political interests of the regime. In short, they are meant to enforce what is described in other countries as “colonial policing.”

At that meeting, the Defense Ministry officials outlined the police’s duties based on two colonial tools at its disposal: the Police Ordinance and the Defense (Emergency) Regulations, both of which were first legislated by the British Mandate in Palestine and inherited by Israel with various amendments. The officials entrusted the police with “the execution of the defense regulations in all spheres: personal restriction orders, closure of areas, etc.” They also entrusted the force with activating the Defense Regulations “to fulfill its role as responsible for the public order in the Arab sector and ensuring the safety of Arab citizens in their towns and in mixed towns [with both an Arab and Jewish population].” In addition, the police were to assist the Israel Land Authority with “safeguarding” land and executing demolition orders.

The protocol of the meeting then explicitly outlines the ties between the military and police to help the latter fulfill their role: “The military commanders will activate Defense (Emergency) Regulations 1945 — apart from IDF needs — only for the needs of the Shin Bet and police. They will not interfere in the professional considerations of these security officials on whose behalf the regulations have been requested to operate. However, since the legal and public responsibility for activating the regulations lies with the military commanders, they are entitled for these reasons to avoid activating them.” The authorities subsequently established two committees to synchronize the policies and operations of the police, military, Shin Bet, and the government advisor on Arab affairs.

Less than four decades after that meeting, in September 2000, the police held a “war game” exercise in northern Israel nicknamed “Storm Wind.” At the opening briefing, the police themselves made a stark, conscious link between the 1948 dispossession of Palestinians and the present-day role of the police force: “…52 years ago, this area, where we are now, was conquered by the 7th Armored Brigade and the Golani Brigade. The exact date: July 14, 1948. And here we are, 52 years later, we still deal with almost the same issues, albeit not conquering the land, but rather guarding it.”

Impunity by design

This colonial heritage of policing is by no means unique to Israel. The police in apartheid South Africa, for example, were routinely called upon to assist the military in quashing protests against the regime and enforcing apartheid laws. Policing was essentially geared toward preserving South Africa’s racial power relations, and dealt, at their core, with the control of movement of the Black population and the suppression of any kind of political resistance.

Another example can be found in the historic role that policing has played in maintaining slavery, segregation, and white supremacy in the United States. That legacy of racist American policing can still be seen today in the way law enforcement metes out brutal violence against Black people and other people of color — a reality which spurred this year’s mass protests across the United States after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Like policing in South Africa and the United States, police in Israel — by design — have no accountability. For example, recent media exposure of the probe into the killing of Ya’qub Abu al-Qi’an in Umm al-Hiran revealed that Israel’s state prosecutor asked the Justice Ministry’s Police Investigations Department (PID) not to investigate the officers involved, and closed the investigation due to political considerations. Likewise, the decision by Israel’s attorney general to shut down the PID investigation into the October 2000 killings and not prosecute those responsible — contrary to the Or Committee’s recommendations — was, in effect, an overt defense of the repressive role played by the police in Israel’s colonial system.

The lack of accountability extends to the killing of Palestinian civilians uninvolved in political events and protests. Since October 2000, dozens of Palestinian citizens have been killed by police without any taking of responsibility. A prominent example was the state prosecutor’s insistence not to charge the officer who shot Kheir Hamdan in the back and killed him in Kufr Kanna in November 2014. In such cases, the colonial heritage provides a wide margin of error for alleged “mistakes” against the policed population, creating a trigger-happy culture among officers.

The refusal to center the welfare and interests of the citizens further creates a deep sense of disconnect, suspicion, and distrust between the police and community. This is most starkly expressed in the police’s systemic failure to solve cases of murder and violence inside Palestinian communities. According to data published in a report of the Knesset Research and Information Center in February 2018, 70 percent of the victims in unsolved murder cases between 2014 to 2017 were Palestinian citizens. A December 2019 Ha’aretz investigation also revealed that only a third of the 91 murder cases in Arab communities that year had been solved, compared to nearly two thirds in Jewish communities.

Gatekeepers of the regime

Viewed through this historical prism, the Israeli police should be understood as the gatekeepers of the state’s colonial legal system; in turn, the decisions of legal authorities to systematically prevent accountability shows that the law is designed to protect those gatekeepers. In this sense, Israel treats its police much like its military — another violent institution which is exempt from liability as it fulfills its colonial duties in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

When apartheid fell in South Africa and the African National Congress came to power in 1994, one of the government’s first tasks was to dismantle and rebuild the national police force. This signaled a new era in relations between the people of South Africa and the state authorities that were meant to represent and serve them.

The post-apartheid police force was constructed, at least in theory, around new social and political principles to reflect that new era. Their responsibilities and duties were regulated by the new South African constitution, as well as new laws that tasked the police to “protect and serve” the community. In spite of this, the ideal police service remains far-off in South Africa since, like many other countries, its police continues to suffer from a culture of violence and politically-motivated impunity, with its behavior mirroring South Africa’s broader class and racial divisions.

However, what we can learn from these other contexts — and from their failures — is that the Israeli police’s approach to Palestinian citizens is inextricably linked to the regime’s political purpose, which in this case, is the intention to preserve Jewish supremacy and control. Thus, to demand the transformation of the police, there must also be the inseparable demand to dismantle the institutional and constitutional power relations that strive for ethnic domination as a whole.

Attorney Suhad Bishara is the director of the Land and Planning Rights Unit at Adalah - The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, and is currently a PhD candidate at King’s College London School of Law. This article originally appeared in +972 Magazine.

Two decades of whitewashing Israel's killing of 13 young Palestinians

Anyone who refrains from investigating and indicting a police officer who aims a lethal weapon at a young unarmed demonstrator shares responsibility for the victim’s injury or death.

By Abeer Baker

2 October 2020

Haaretz

As fate would have it, I entered the human rights community following the killing of 13 young Palestinians. They were shot to death by police in central Israel and the Galilee exactly 20 years ago. I eventually joined the legal team at Adalah – the Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, which represented the families of the slain.

The generation I belonged to was the “stand tall generation,” which demanded recognition of the elements of our Palestinian national identity as an integral part of our Israeli citizenship. This generation’s erect posture was suited to a legal battle waged by citizens to exert the full force of the law against those responsible for their bereavement, which was both personal and national.

Twenty years after those events, my conclusion is that if anything was crushed and eroded by the force of this battle, it was our faith in the use of legal tools to obtain justice for the victims, to the point where it seems that all that remains of the upright generation are the families and the headstones on the graves of the slain.

The whitewashing of the circumstances of the death of Yakub Abu al-Kiyan, an educator, in 2017 is a kind of microcosm of what happened two decades ago and continues to this day. Back then, as now, the state prosecutor and the attorney general refrained from any direct, public criticism of the police and its snipers, even though a state commission of inquiry headed by then-Justice Theodor Or concluded that the police shooting that killed the 13 young protesters was unjustified.

Then, too, law enforcement officials refrained from criticizing the Justice Ministry department that investigates police misconduct for its criminal negligence in investigating those incidents, in which so many citizens were killed and wounded. But back then, the chutzpah was even more overt. The officials responsible didn’t operate in darkness, under the cover of internal correspondence that the law theoretically allows to remain classified, the way former State Prosecutor Shai Nitzan did in the Abu al-Kiyan case.

Back then, the state prosecutor and the attorney general didn’t hesitate to publicly back the Justice Ministry department shortly after the closure of the cases against the police officers was announced. They did so even though by law, they are the people to whom the department’s conclusions can be appealed if the bereaved families so choose. Their need to defend “our brothers in investigating the killing of Arabs” forgot what their official roles are and failed to offer even a pretense of fulfilling them.

The state prosecutor didn’t hesitate to publicly back the department, which he is supposed to oversee, even though he was one of its founders and its former head. The term “conflict of interests” is relevant to law enforcement officials only when they accuse others, not, heaven forbid, when the accusations relate to their own jobs.

But both the attorney general and the state prosecutor outdid themselves when they decided, on their own initiative, to review the department’s findings, which they themselves had backed just a few days earlier. They conducted the review themselves, and it resulted in Attorney General Menachem Mazuz issuing an embarrassing document in 2008 that contradicted the Or Commission’s findings and backed the department’s failed, obstructive investigation, which legitimized a violent concept of policing identical to military doctrine, which sees protesters as enemies who must be defeated.

The families have been watching this whitewash of the investigation into the killing of their loved ones for 20 years now. In today’s terms, the families could accurately be described as active crime victims. The pain of their loss never undermined their strength in fighting for the implementation of their just demands.

They never missed a single meeting, a single public event or a single press conference. They made sure to study and understand the process from start to finish. They heard with their own ears how their sons were killed, and some even saw with their own eyes as the people who killed their children took the witness stand and brazenly lied. They carried signs, marched through the streets and heaped criticism on their political representatives.

Thanks to the families’ years of protests, we, the lawyers, were exposed not just to the unsurprising result that the officers were given immunity, but also to the tainted process of investigating the truth and the failure to bring those responsible to justice. For us, the families defined what it means to be responsible for a person’s right to life, beyond what we had previously known. Thanks to them, we learned that a state that doesn’t conduct a swift, proper, unbiased investigation into its citizens’ deaths at the hands of its own armed forces blatantly violates its obligation to respect its citizens’ right to life.

Anyone who refrains from investigating and indicting a police officer who aims a lethal weapon at a young unarmed demonstrator shares responsibility for the victim’s injury or death. The statute of limitations on responsibility for this investigation’s failures hasn’t expired even after two decades. But perhaps, two decades after these events, somebody, somewhere, will come to his senses and decide to do his job properly.

Abeer Baker was part of Adalah’s legal team which represented the families of those killed in October 2000 before the Or Commission and other bodies. This article originally appeared in Haaretz.

CLICK HERE or on the above image to learn more about the October 2000 events